Jean Smith performing for a captive audience on a ferry crossing a lake in BC on the Black Wedge tour 1987.

The Black Wedge Tours

by Jean Smith

Excerpt from American Book Award winner Sounding Off — Music as Resistance / Rebellion / Revolution

1996, published by Automedia, ISBN 1-57027-058-9

Edited by Ron Sakolsky and Fred Ho

Take Something You Care About and Make It Your Life — Jean Smith

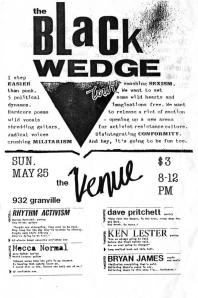

“One step easier than punk! The Black Wedge is out to spread the word of how to combine poetry, music and politics and have a fun time doing it. Hardcore poems and shredding guitars, radical voices crushing sexism, militarism, poverty and conformity. The Black Wedge wants to set wild hearts and imaginations free, to release a riot of emotion–opening up a new arena for activist resistance culture.”

In the early part of 1986, Mecca Normal released their first LP on their own label, Smarten Up! Records. Soon thereafter, they flew to Montreal and hooked up with Rhythm Activism; another voice and guitar duo dealing with social concerns from an anti-authoritarian perspective. While the four stood around in the basement of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation building waiting to go on live radio coast to coast, they listened in on the segment prior to their spot–England’s Red Wedge was being featured. Formed in the late ’80s to support the Labor Party, the Red Wedge presented political ideas within a musical context, a showcase of musicians encouraged people to vote Labor. The Black Wedge, coming into existence that night, would encourage people to reclaim their voices, to speak out against oppression rather than rely on electoral politics as a means to solve social problems.

A phone call was made to Vancouver and a bus was secured for a West Coast tour. The tour line-up included Mecca Normal, Rhythm Activism, Ken Lester (D.O.A.’s manager, activist and poet), Dave Pritchett (longshoreman and poet) and Bryan James (a self-describe “jingle man”).

Leaving Vancouver after a sold-out show, the tour headed south, playing nightclubs, a bookstore, an art gallery, a soup kitchen, a record store, universities and as many radio stations as possible along the way. Our preliminary promotional work paid off, and articles appeared in many publications, including mainstream daily papers.

The show, divided into five segments, dealt with a variety of issues. Mecca Normal performed “Strong White Male,” “Smile Baby,” and “Women Were King”–all of which brought up sexism and male oppression. We also performed “Are You Hungry Joe?”, a dialogue between Joe and the guy that stood between him and a bag of groceries at a food bank. Rhythm Activisim also addressed poverty in “The Rats.” Bryan James’ songs were about pornography and the lure of the TV screen. Dave Pritchett’s poems were mainly about disenfranchised citizens and lost love. Between songs and poems, we all talked about what we were trying to do with the Black Wedge. Sometimes it sounded dogmatic and rhetorical, other nights it was spontaneous and charming. In Olympia, Rhythm Activism’s Norman Nawrocki called for a raid of the Safeway next door–it didn’t quite happen, but there was enthusiasm for the plan.

As a group, the Black Wedge was grappling daily with the same concepts that we pontificated about from the stage nightly. In San Francisco, Bryan and I published a small newsletter called Bus Tokens. We distributed it that evening at the show. I was the only woman on the tour and Bryan is black, the rest of our tourmates were white males. In a somewhat frustrated tone, Bus Tokens railed against authoritarian attitudes on the bus, sexist comments and personal gripes. As a group, we presented a show to inspire people, to introduce the possibility of creating poetry that was aggressively useful and music that was stripped down to the powerful basics of guitar and voice, but as the tour evolved and people became more frayed, I became more aware that we had created a microcosm of what we were expressing opposition to. I think people who address social concerns are expected to be beyond reproach. With the Black Wedge tours and subsequent politically based endeavors, it became very clear that there was no purity in this type of work. There was no path laid out in front of us; mistakes were made, experience altered our approach. It seems like people tend to wait for a signal to start a project; the strange thing is that once you start a project, you forget about the beginning, you are too busy dealing with the stream of problems and opportunities that follow.

HOLLAND, 1994

I am sitting outside at a cafe table in Holland with David, our traditional breakfast arrived, salami and a white bun. I order a beer and use the salami to shine my boots.

“It seems like music and philosophy have cut themselves off from life, they ignore each other, they used to feed each other,” says David, continuing our ongoing conversation.

“As far as music goes, there’s an agreed upon obligation to create replicas of what’s already in front of us,” I say. “It seems like the one thing necessary to make something of value is the thing we’re encouraged to hide. Difference. The thing that makes us different from each other.”

My beer arrives, filled with bubbling amber in the slant of morning sun. I am looking at the back of the cafe wondering what the rectangular black shapes on the far wall are, I realize they are other rooms.

“Success seems to be viewed in terms of ability to imitate. Who told us to stop making up life as we go along? It’s funny how we’ve traded political rights for consumer rights, we’ve been reduced to buying and selling popular concepts, guzzling approval. Who’s trying to create anything?”

Prior to the Black Wedge, Mecca Normal had not toured at all. That first tour was amazing; we met poets, community activists, anarchists, feminists, people at radio stations, recording label people, fanzine writers and bands. It was incredible to drop into a community and see what was going on and, at the same time, represent ourselves. I don’t think we had any idea of what was out there in terms of like-minded people. Since that first time out, Mecca Normal has done about thirty tours in North America and Europe. After the group tours, we became more insulated, preferring to tour by ourselves and play on regular rock bills as a contrast to the four-guys-on-stage syndrome.

In 1987, the Black Wedge got on the same old school bus and drove from Vancouver to Winnipeg. Rhythm Activism, Bryan James and Mecca Normal were on the bill again in addition to Toronto’s Mourning Sickness–“committed to destroying all forms of patriarchal power…” and Peter Plate, an agent of the spoken word, who had seen our San Francisco shows the year before and decided to join us. Responding to an ad in Open Road, an anarchist news journal, Nelly Bolt took on the driving and information table with anarchist news, Black Wedge booklets and prisoners’ rights information. David Lester set up a display of political posters at every show. Booklets containing a selection of everyone’s work and a compilation tape were sent out to secure shows. One promoter in Edmonton canceled our show after hearing Peter Plate’s piece “San Bernadino” in which, to paraphrase, Peter jerks off on church door handles Saturday night so his dried seed will glisten on the priest’s hand Sunday morning. Konnie Lingus of Mourning Sickness brought up the rights of sex-trade workers, herself being one. Prudence Clearwater and Lynna Landstreet were the other band members. When we met up with Mourning Sickness for a Toronto show, Prudence had been attacked by a man on a street the night before. She was so strong up on stage doing her usual rant against street harassment, “Listen to me, little man,” she howled down at the audience. It felt like our introspective world touring had been interrupted by reality.

On a ferry ride across a lake in British Columbia, Peter jumped up on the roof of the bus without warning and began a poem. The other passengers tried to pretend this was not happening; people in cars actually rolled up their windows. Nelly Bolt, our driver, also got up there and did her first public performance of her poetry to a captive audience.

In ’88, Peter Plate and Mecca Normal went to England to perform on the cabaret circuit. We were sandwiched between highland dancers, comics, and skits. Peter was dynamic; all his pieces were done from memory. Mecca Normal had always wanted to be either a contrast to a larger, more traditional rock band, or as part of the Black Wedge, an element within a similarly motivated group. In England the other acts were entertainment, something we never wanted to be!

After the tour ended I stayed in the North of England doing solo readings and running a women’s writing workshop which was set up for me by Keith Jafrate, a poet, sax player and an employee of the local council. He was running writing workshops at all different levels involving poets and people interested in improving their writing skills. Keith joined the ’89 Black Wedge tour in North America. He teamed up with Rachel Melas on bass. We were joined again by Peter Plate. We toured the West Coast and in the East before the thing exploded for financial and personal reasons. That was the last tour that I know of called the Black Wedge. The name is available for other people to use to present anti-authoritarian ideas. It is meant to be an arena for people who might not otherwise be known well enough to bring out an audience. It was never meant to be a closed group that was only active for a short time.

Bicycles are moving throughout the city at the end of a journey, they are left for the next person to use.

If the Black Wedge shows themselves were not consistently well attended, we did get air time and press, not only at college stations and in leftist publications, but on national radio (Canada’s CBC and England’s BBC); regional glossy magazines appeared with photos and major dailies ran features. We felt that pushing our ideas about anarchism into mainstream culture was important, and we succeeded. The headlines read, “The Black Wedge spreads the word,” “Anarchist poetry to the fore in the war against social injustice,” “Paint it black,” “Black Wedge strives for the subconscious,” “Feminist aggro in the Black Wedge,” “Wedgies are back!”

The Black Wedge functions/agitates in the crawlspace of resistance, under the big house of capitalism.